Yesterday , I referred to a post by Peter Phillips, Reflecting on metropolitan ecumenism and grassroots mission . The idea of metropolitan ecumenism intrigues me. Phillips implies he found the term elsewhere but I have found no other references to it following a Google search. This is Phillips' definition:

Yesterday , I referred to a post by Peter Phillips, Reflecting on metropolitan ecumenism and grassroots mission . The idea of metropolitan ecumenism intrigues me. Phillips implies he found the term elsewhere but I have found no other references to it following a Google search. This is Phillips' definition:

So what is meant by metropolitan ecumenism? Basically, to me it means ecumenism that is handled in London and by central office - hierarchical ecumenism - top down ecumenism. My own first reaction to the speech was a good example - I went back to statements which had been issued by high-ranking meetings and agencies. I went to the central tenets of Methodism and agreed wholeheartedly with what David Gamble said. I argued it was fully in accord with what Methodists say about the Covenant and fits in well with that Covenant (and see the others who say the same within the same metropolitan media-style ecumenical perspective above). I'd stick with that and I don't think there is anything wrong with such a viewpoint. But the very danger is that we do stick there. Sometimes we get set into a kind of networked mindset - where academics involved in a network end up in an ivory tower which is really helpful for their own research but misses the point of what is actually happening on the ground. Metropolitan ecumenism is only as good as ecumenism on the ground. We cannot and will not see unity within the Church through the dictat of any Synod or Committee. Unity comes from the grassroots but can be enabled and empowered by metropolitan enthusiasm.

On a practical level, metropolitan ecumenism might be a useful phrase to describe what I have tended to call 'central' or 'national' ecumenism. I think the distinction between metropolitan and local is an important one and I have addressed it several times on this blog under the name of ecumenical reception .

Some may find Phillips' point 'Metropolitan ecumenism is only as good as ecumenism on the ground' old hat but it is well made. What he is describing is two contrasting and sometimes opposed mindsets. His purpose is not, as I read it, to oppose metropolitan and local ecumenism but to describe a relationship between two complementary approaches. Metropolitan alone will be divisive and could pull the church apart if it moves without the support of the local; it will also lack insights from innovative local ecumenical work. It is too easy for theory to cloud judgement and this is why in yesterday's post I suggested that each ecumenical step must be followed by reassessment before the next. The Anglican Methodist Covenant was signed in 2003 and it is still too early to understand the impact it is having on our churches. If we achieve interchangeability (the likely next step), we will likewise need another reassessment before planning the next. This is essential for reception of changes: moving at a challenging pace local churches can support.

Without the metropolitan perspective, the local can lose track of its calling to be the church in a particular place. The temptation locally is to elide differences and lose the distinctive marks of the churches employed in local mission.

The tense relationship between local and metropolitan is potentially fruitful so long as they listen to one another.

Sometimes there is vehemence on the part of some local churches, expressed through disparaging terms they use of metropolitan leadership. I suspect this may be explained to a degree by a distinction highlighted by Diarmaid MacCulloch in A History of Christianity . In a section beginning on page 622, MacCulloch contrasts the Magisterial and Radical Reformations. The magisterial approach refers to magistrates. Reformed Christianity began as Christianity run by the state, that is the magistrates of cities such as Zurich. The Radicals were those who would submit to no such authority, eg the Anabaptists.

This question reverberated throughout the Reformation: how do we determine the appropriate authority for our churches? This long history, means there can be. amongst local churches, a suspicion of the hierarchy of their churches. This is not necessarily a bad thing, if it means initiatives from the authorities are questioned. Since all churches need some sort of metropolitan organisation, although there are many ways of structuring it, reception is an issues for all churches.

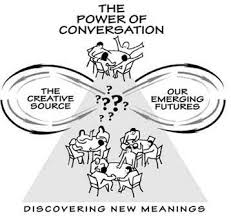

The need is for local and metropolitan to find a means to dialogue. Problems begin where they forget to dialogue or refuse to engage with each other. Such dialogue is not necessarily easy and I have elsewhere written about the need for ecumenism with many tables . This way conversations locally can feed into the metropolitan conversations. There will always be tensions but that is not inevitably a bad thing.

Comments