The Penguin English Dictionary defines subversive as 'tending or attempting to undermine authority, established ideas, etc'. I like this definition because it places subversive somewhere between active and passive. It is an equivocal definition, so that subversion tends, or attempts, not to destroy but to undermine. Of course, some people won't like the word because it questions authority in the churches. If you are one of them, stay with me; the choice is not between authority and subversion.

The Penguin English Dictionary defines subversive as 'tending or attempting to undermine authority, established ideas, etc'. I like this definition because it places subversive somewhere between active and passive. It is an equivocal definition, so that subversion tends, or attempts, not to destroy but to undermine. Of course, some people won't like the word because it questions authority in the churches. If you are one of them, stay with me; the choice is not between authority and subversion.

This phrase 'Subversive Ecumenism' came out of a paper I was invited to write called 'The Discipline of Subversive Love', where I chose to examine ecumenism as subversive love. I presented this paper on 22 May 2010 and some of the issues arising are listed in a post two days ago. This short series will present a more coherent exploration of the idea. What exactly is subversive ecumenism?

I suspect many people will have less problem with the idea of subversive love than subversive ecumenism. The principle that love might undermine prevailing authorities, is common in the stories Christians tell one another. Indeed, the sort of love that leads to the cross is bound to be subversive of those authorities who habitually use instruments of torture and death. Even in a modern Western democracy, the non-violent lifestyle, faithfully lived, can still be threatening to authority.

The idea of 'subversive ecumenism', unlike subversive love, is clearly an oxymoron. The first word implies a degree of lawlessness, of thinking and acting outside the box. The second implies authority experienced as respect for the faith and order of the churches. How can ecumenism be subversive? Surely its purpose is to reconcile divisions rather than undermine existing authorities?

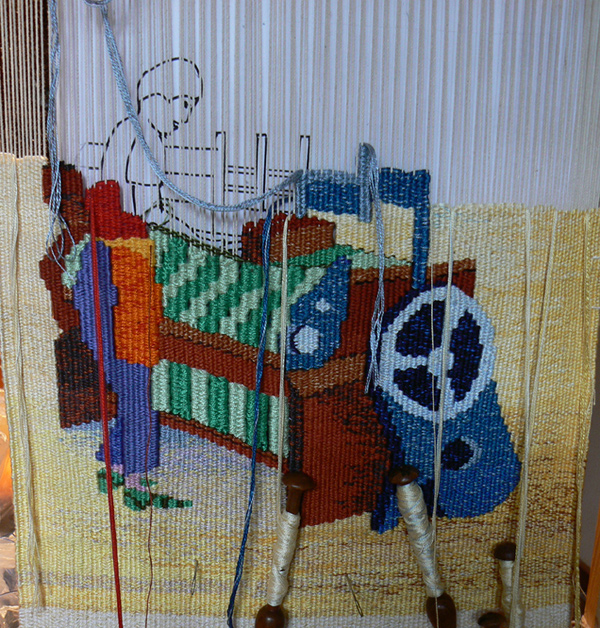

Perhaps subversion is what we need, when we contemplate the 'ecumenical winter'. I recently reviewed the paper Fine Nets and Stratagems by Mark Langham, which offers a good account of the current ecumenical impasse. His paper addresses in a compelling way, means by which this log jam might be moved. Whilst a great deal has been achieved by the faith and order approach, the remaining problems are inevitably much more intractable. If the denominations have weaved a rich tapestry during their ecumenical conversations, there is a feeling this tapestry, including the churches themselves, is unraveling.

One of the features of the ecumenical winter is the prevalence of new informal churches, outside of the main denominational bodies. One reason for this is these informal churches represent groups who, for a variety of reasons, feel marginalised within the traditional churches.

Complexity theory explores how rich patterns emerge on the boundaries of order and chaos. Even though it may seem subversion is the last thing we need, I wonder whether it has a role facing authorities at the chaos/order interface? If we consider the Methodist / Church of England conversations, for example, those engaged in the Faith and Order conversations rarely encounter those active in fresh expressions. If fresh expressions to some degree undermine the authority of the two churches, we can see the potential for the two to go their separate ways, unless they are intentionally brought together.

The remarkable thing about the ecumenical spirit is the demand it makes upon us to love each other across doctrinal differences. Our differences are seen as reasons to love, rather than as barriers to love. The ordered and the chaotic need each other, if they are to be fully alive and creative.

Subversive ecumenism needs something to subvert. Church authorities need to be challenged by those who are on their margins. So, we need a wider ecumenism that embraces both formal and informal. Out of this conversation, this whole church oikoumene, will emerge new patterns of church and of practical ecumenism.

Comments